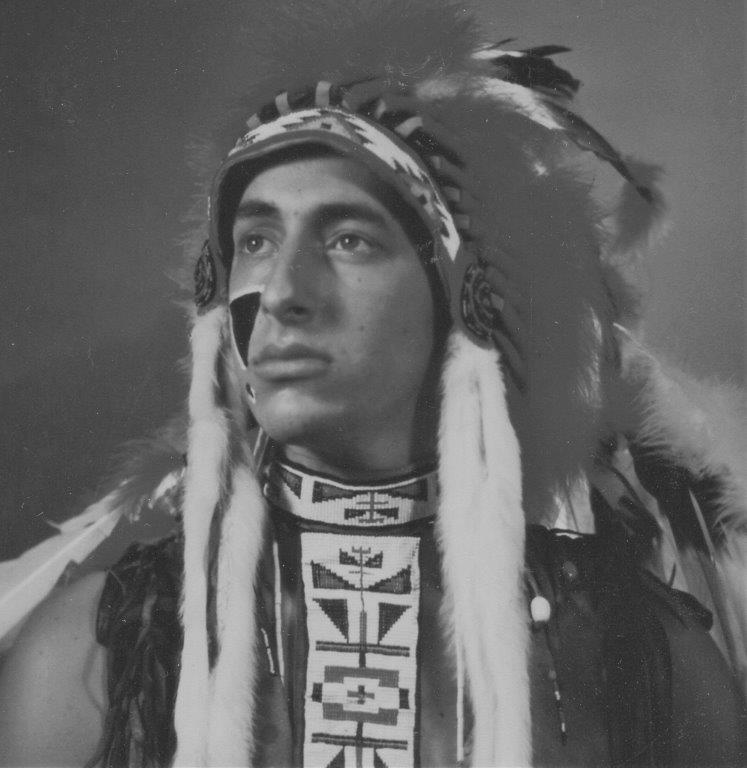

Kocsis was born on April 27, 1936, in Buffalo, NY, the son of Geya Kocsis, who worked at Bethlehem Steel Corp., and Marion E. Kocsis, née Whitbread. At age six Kocsis moved with his parents to Bethlehem, PA. He began painting at age 12 after receiving a small set of oil paints from his parents for Christmas; noting his enthusiasm and talent, his mother arranged for private lessons. Kocsis developed a deep interest in American Indian art and culture, particularly the songs, dances and rituals of the Seneca tribe of upper New York state. He spent many summers at youth camps teaching American Indian traditions.

In 1954 Kocsis was awarded a four-year scholarship to the Philadelphia College of Art (now University of the Arts), where he studied under and was influenced by painter and printmaker Jacob Landau. His artistry was also influenced by sculptor, draftsman and graphic artist Leonard Baskin. Upon graduation in 1958, Kocsis enlisted in the army. He was stationed for 19 months in Germany and travelled extensively across Europe drawing, painting and visiting museums. In January 1961, after returning to the United States, Kocsis married his college sweetheart from Philadelphia College of Art, Carol Virginia Frearson, who became a favored model for Kocsis’s paintings.

From 1961-68, Kocsis lived and worked in the Germantown neighborhood of Philadelphia and focused on perfecting his draftsmanship. Using the pseudonym J.C. Kocsis, he illustrated more than 20 books and drew the illustrations for Edge of Two Worlds (1968) by Wayland Jones, which won the 1969 Lewis Carroll Shelf Award. The illustrations were exhibited at the American Institute of Graphic Arts, which in 1968 awarded Kocsis AIGA’s biannual award for excellence. In 1965-67, Kocsis taught drawing and pictorial composition at his alma mater, the Philadelphia College of Art, and was a lecturer at Kutztown State Teachers College, now Kutztown University.

In 1968, feeling personally and artistically constrained by assembly line drawing, Kocsis turned from his budding career as an illustrator and went into seclusion to paint full-time. His education, experience teaching and work as an illustrator gave Kocsis a strong foundation in the technical elements of painting and a keen understanding of the evolution of modern art in America and beyond.

As a painter, Kocsis developed his own unique style, with brilliant colors layered in thick sweeps of oil paint. He almost exclusively painted portraits of people who posed in his studio. Kocsis selected models from friends, patrons and people he recruited from the street. His subjects ranged from ballerinas to poets, dwarfs, politicians, cross-dressers, athletes and others.

Joseph C. Skrapits, in his 1981 book “Kocsis: The Art of James Paul Kocsis,” noted the influences of post-impressionists, expressionists and surrealists that ally Kocsis with Cezanne, Van Gogh, Fauvist Matisse and Kandinsky, among others.[i] According to Who’s Who in American Art, Kocsis pioneered a painting style known as “psychic impressionism.”[ii]

When Kocsis invited subjects into his studio, he demanded intense concentration, absolute stillness, and fulltime eye contact. Kocsis – with headphones blasting classical music that drowned out all other sound – often painted in a trance-like state in which he achieved an almost mystical connection with his subjects. Depending on the inspirational spark, the sessions could yield highly expressionist portraits, with brilliant flame-like splashes of paint that captured what Kocsis perceived as the subject’s soul and essential humanity. Other times, the paintings were extraordinarily realistic and deeply emotive, which Kocsis said reflected the intense love he felt for his models while painting them. In some paintings, particularly ones from early in his career, it can be difficult to discern human features. In others, there is a fine attention to facial detail, particularly, often, the subject’s eyes.

In his early “primitive” paintings, Skraptis wrote, Kocsis had a “savage intensity,” reflecting both the turmoil of American society during the Vietnam era and in his life. But as he matured as a painter, Skrapits said, Kocsis’s style became “lighter and more lyrical,” with greater atmosphere and “abstract rhythms.”[iii]

Kocsis’ impressionism, Skrapits wrote, “is not merely a representation of optical phenomena – the changing conditions of natural light as it falls on objects – but a kind of ‘psychic impressionism’ through which the aura of spiritual light which surround the figure is suddenly visible.”[iv]

Art dealers were attracted to Kocsis’s new and distinctive style and sought to influence and control his creative output. But Kocsis rejected their overtures, deriding them as part of a collusive fine arts “syndicate” of museums, gallery owners, and art dealers whose aim was to entangle artists in contractual relationships and get them to “sell out.”

“The artist is typically screwed out of the fortunes created by these efforts,” Kocsis said in a long 1987 interview with Judge Raymond E. Kramer, who Kocsis painted in the 1970s. “The rich become richer and the artist is bought for as little as possible, exploited as fully as he can be exploited. And he’s up against a tremendous barrage of ruthless, shrewd, cunning, experienced professionals. In most cases, the beauty of the creative process and the art form that he creates, his creation, which is alien to the reality of the business world, dies. I don’t see where the artist ever stands much of a chance at all of surviving, of getting anything but screwed.”[v]

Kocsis became defiantly independent and at times reclusive, rejecting what he felt was the corrupting commercialization of art. He lived in fear of being preyed-upon by the “art-industrial complex,” on the edge of a nervous breakdown and in a state of self-described paranoia that lasted several years. The conflicts between art and commercial pressure, the battles Kocsis waged against his own demons and the conventional art world, and his obsessive fear of exploitation were documented in the 1999 book “Kocsis Scourged: Surviving the Art World,” by Dr. Albert Nekimken.

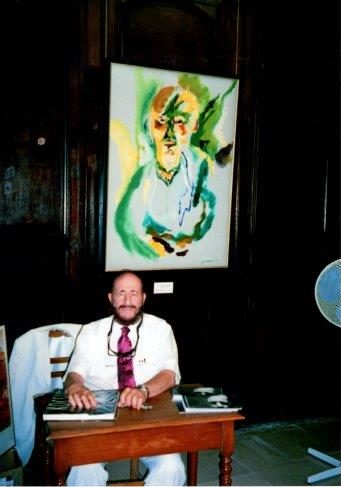

Because of the fear of being exploited and corrupted by galleries, dealers and other people who Kocsis believed wanted to dictate what he painted and how, Kocsis managed all of his own business affairs. Even with the help of his wife and friends, it was an extraordinarily time consuming and expensive — but essential — part of Kocsis’s life and art: the price he paid for artistic freedom. He would lay down his brushes and painting scalpels for years at a stretch to focus on promoting his art and scheduling exhibitions, frequently overseas. Then he would return to his studio for an explosive period of production during which he would typically create dozens of paintings.

“The artist must accept his business responsibilities as seriously as his creative ones,” Kocsis explained in a 1992 interview with Nekimken, the author of “Kocsis Scourged.” “It’s not enough to just create the art itself – if it is the real thing. The natural process will be to follow through and establish your own links to the public and to collectors…For me personally, based on the intensity of my painting, the business elements are a balance to other elements in my life. The freshness, the perspective and the reinforcement – physically, mentally and spiritually – that the balance of all these artistic and business elements offer has been very rewarding.”[vi]

Over 30 years of production, Kocsis arranged 42 shows in more than two dozen countries on six continents, in venues as far away and diverse as Australia’s Sydney Opera House (1979), Trinity College in Oxford, England (1988), the Martin Luther King Center for Non-violent Social Change in Atlanta, Georgia (1990), the United Nations in New York (1991), the Gandhi Peace Center in New Delhi, India (1995), the Hermitage Museum Library in St. Petersburg, Russia (2005), and the Eglisé St. Germain l’Auxerrois in Paris, France (2009).

Kocsis stopped painting in 1999, having produced more than 500 paintings over three decades. He explained to friends that, with such a large body of work – and given the time, expense and energy it took to handle his promotion, exhibitions and sales – he felt the need to dedicate himself full-time to the business aspects of his life.

Kocsis died in Allentown, PA, on December 28, 2021. He is buried alongside his wife Carol at historic Nisky Hill Cemetery in Bethlehem, PA.

Footnotes:

[i] Joseph C. Skrapits, Kocsis: The Art of James Paul Kocsis (Lehigh Valley: Paragon Press, 1981) p. 86-92

[ii] Who’s Who in America, Supplement to 44th Edition (1987-88).

[iii] Skrapits, Kocsis: The Art of James Paul Kocsis, pp. 103-4.

[iv] Skrapits, Kocsis: The Art of James Paul Kocsis, pp. 90-1.

[v] Dr. Albert Nekimken, Kocsis Scourged: Surviving the Art World (Lehigh Valley: Paragon Press, 1999) P. 123

[vi] Nekimken, Kocsis Scourged: Surviving the Art World, p. 185.

"Commercial fine art, like illustration, is created to serve a purpose. True fine art has no utilitarian purpose beyond its own existence."